La Paz, April 20, 2025 (ABI) – Accompanied by severe pain in her lower abdomen, she got her first menstruation when she was barely 12 years old. When she discovered that her underwear was stained with blood, she was frightened and ran to tell her mother.

“My mother told me that throwing blood around was normal and my friends commented that on those days you shouldn’t touch water, you shouldn’t bathe,” recalls Jhanet Villa, 23, as she breastfeeds her eight-month-old baby, takes care of her other two-year-old child and sells klinex (disposable paper) and mentholated candy on the sidewalk on Mariscal Santa Cruz Avenue, in the center of the city of La Paz.

She often arrives, along with her two young children, to the city of La Paz to earn a living for her household. She is a native of the municipality of Sacaca, capital of the province of Alonso de Ibáñez, in the northern region of the department of Potosí.

She studied only up to the second year of high school. She remembers that, both at home and at school, she was hardly told about menstruation. The first sanitary napkin she used was a gift from her mother. But as she grows into adulthood, with the little she earns, she can sometimes buy a packet and sometimes not. “Money is not enough,” she says.

According to UN Women “every month more than 2 billion women in the world menstruate”. And Unicef explains that it is important to understand that “menstruation is a natural and normal biological process that all women go through, it is not a disease, nor anything that should cause shame or fear”.

“Menstruation or menstruation is a natural and healthy process, yet millions of women and girls cannot access menstrual products or access to safe water and sanitation to manage their menstrual health and hygiene. This is something that truncates their lives, their rights and their freedom,” the publication states.

But what do experts and teachers in the country say?

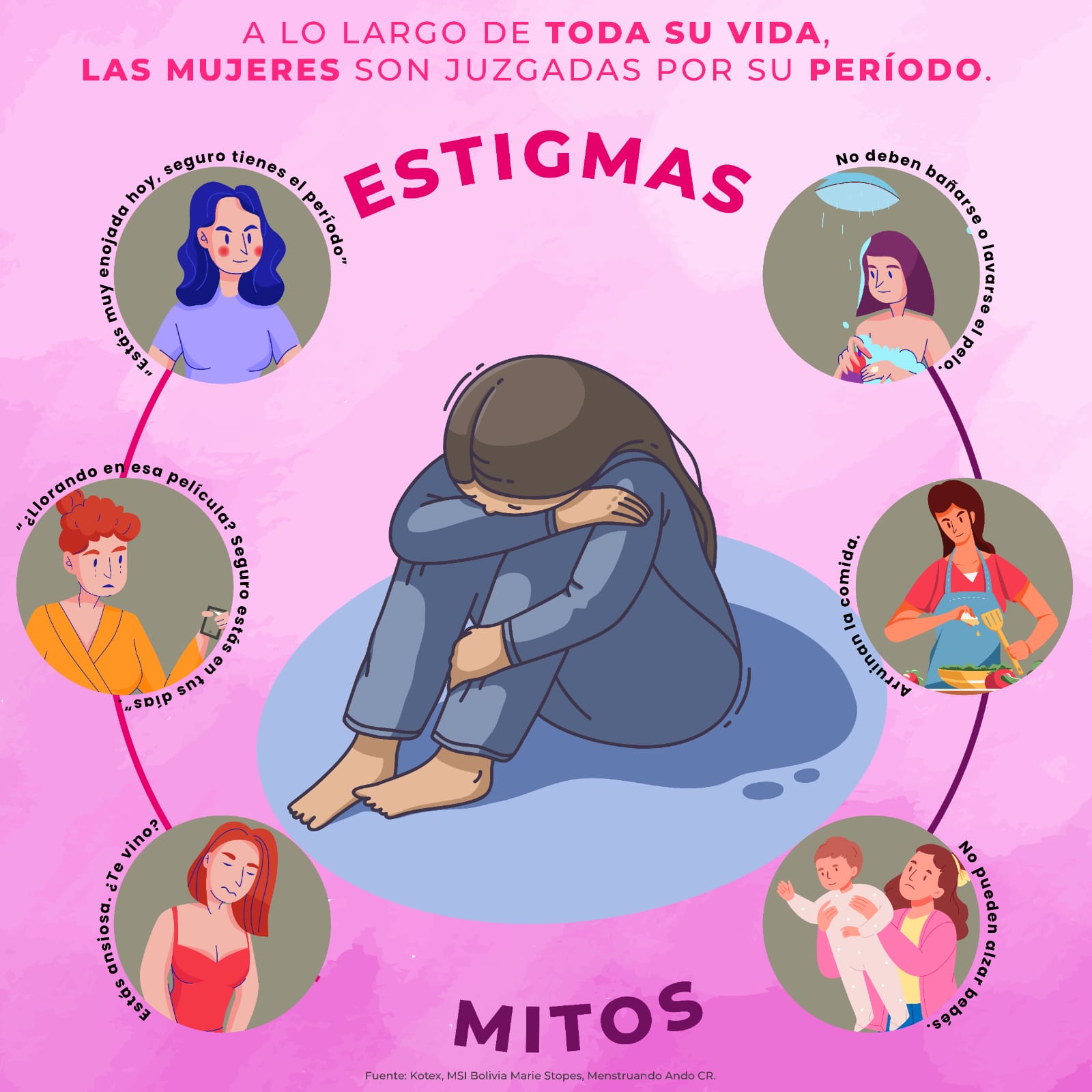

In an interview with ABI, Silvia Velasco, manager of MSI Bolivia’s Marie Stops Clinic, assures that in the country “over time there has been greater awareness of how to deal with menstruation”. However, although this topic is talked about, there are stigmas and taboos and this is due to the lack of education on the subject.

“Whether you go to the highlands or the lowlands, there are beliefs and myths related to menstruation and they are always negative. The State has to take a position and talk about menstrual health through schools,” adds her colleague Leandra Ruiz, an educator with the same international Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) specializing in Sexual and Reproductive Health.

For the expert, Comprehensive Sexuality Education must be provided by teachers and she dares to assure that many “did not have any education on this subject”.

“It is very difficult to tell them to talk about a subject that, sometimes, their own values are against or they have many prejudices. They have not gone through a process of sensitization, of training, to be able to really transmit this message,” he explains.

But the first edition of the Teacher’s Guide on Comprehensive Sexuality Education (EIS) of the Plurinational Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures (Ipelc), a decentralized entity of the Ministry of Education, carried out with technical assistance from UNICEF and funding from the Government of Canada, in the framework of the program “Empowered adolescents to prevent pregnancies, HIV and violence in Bolivia”, to which this newspaper had access, addresses the topic of menstruation.

Information on the menstrual cycle, pre-menstrual syndrome, menarche, menstrual hygiene, menstrual hygiene resources or articles, intimate hygiene and menstrual care can be found in sections of this text.

“There are guidelines for teachers on how they should approach Comprehensive Sexuality Education. The problem is that it is not being applied in the same way in all educational units. There are educational units that directly do not do it, or do it very little, very superficially, and there are others that do make an attempt,” Ruiz questions.

René Aruquipa, director of the Elizardo Pérez Educational Unit (UEEP), located in the Ballivián area of the municipality of El Alto, recognizes that topics such as menstruation “should not only be known by women, but also by men” and suggests that it is necessary to deepen Sex Education in schools.

However, his colleague, Abdón Suñagua, a professor of Philosophy and Psychology during his 30-year career at UEEP, observed that students in the first and second years of secondary school were embarrassed when the subject was broached in the class that touched on “biological changes”.

“At times we have had complaints from some parents: ‘How are they going to talk about these things, that’s for adults (…)’. There is no open communication on this subject and the children are being formed this way,” she regrets.

Menstrual poverty” in Bolivia

Leandra Ruiz states that in Bolivia, as in other countries, there is “menstrual poverty” and this refers to the impossibility of accessing, due to lack of economic resources, products for menstrual management and hygiene, such as sanitary napkins, for example.

“Access to menstrual management products is scarce, especially in rural areas (…) There are no subsidies for access to sanitary pads, and they are taxed at quite high rates, which makes their price unfavorable for everyone,” says the educator.

This means, says Ruiz, that many women have to decide between eating or buying a menstrual hygiene and management product during the days of their period. Pads, for example, are considered an “almost luxury” product and can cost the same or more than lunch.

“This means, rightly, a significant violation of human rights,” he reflects.

In the La Paz market, a package of sanitary napkins currently costs from Bs 11 to Bs 15, depending on the quality and brand, which is mainly imported. But there is not only this product for menstrual management and hygiene, there are also tampons, menstrual panties and menstrual cups.

Taking into account that a package of disposable sanitary pads currently costs Bs 12 in the La Paz market and a woman menstruates for about 40 years, it is more or less Bs 5,760 that is required for menstrual management in that time.

Considering these data and thanks to her sewing skills, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2020, Yanina Valencia made her own handmade, handmade and ecological sanitary towels. Although at first it was for her personal use, she later decided to market them to other women.

Thus, it created the brand Esencia Toallas Ecológicas, based in Santa Cruz. It is a Bolivian enterprise dedicated to the manufacture of cloth towels, in four varieties, which cost from Bs 25 to Bs 50.

The curious thing about ecological sanitary napkins is that they have a useful life of three to five years. In that time of durability, one can save Bs 1,000 or more, taking into account that some people spend from one to three packs of disposable sanitary napkins every month.

But beyond offering an economical and environmentally friendly product, Valencia also offers workshops on menstrual education and even making ecological pads. This initiative reached girls, adolescents, young women and mothers not only in Santa Cruz, but also in Sucre.

“There I realized the need for menstrual education in all educational units (…). There were many cases in the school that made fun of the classmates when they found out they were menstruating or when they accidentally stained their uniforms,” she says about her experience.

These situations motivated Valencia to create and disseminate on Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, educational content about menstruation, because “such basic and important topics not all people talk about it openly, they are still ashamed”.

Toilets, water and hygiene

In addition to the economic factor, menstrual management and hygiene involves access to water and basic sanitation. According to official data, as of October 2024, Bolivia had 88% access to water and 65.15% basic sanitation coverage.

“Access to restrooms, mainly in peri-urban and rural schools, is complicated; there is not very good hygiene in them. Many girls cannot change their menstrual pads at school,” said Leandra Ruiz of MSI Bolivia, Marie Stops.

The survey on menstrual hygiene in Bolivia conducted by Unicef’s Ureport in the country’s nine departments, published in 2024, revealed that 65% of the women consulted responded that the bathrooms in their schools are not comfortable or clean and that they are not always open.

Fifty-seven percent asked for better cleanliness in these restrooms, including better management of garbage. 56.9% said that the restrooms should have cleaning implements, such as soap, paper, and others. And 23% responded that the restrooms in their school are not in working order and ask for repairs.

The project called “Menstrual Hygiene Management Impacts the School Experience of Girls and Adolescents in the Bolivian Amazon”, funded by the Government of Canada, implemented with the support of Unicef and other institutions, interviewed adolescents and girls from rural municipalities in Beni in 2015 on this topic.

“During the interviews with the adolescent girls, they stated that the bathrooms were in poor condition, lacked maintenance, smelled bad and were dirty and that there was no soap or water available. The girls said they did not like to use the toilets in the educational unit and usually went home at any time if they needed to go to the bathroom, especially during their menstrual period,” reads a section of the report of that project carried out 10 years ago.

Liliana Oropeza, co-founder of the Yawar project, adds that “access to water is becoming more and more of a problem” in regions such as the Bolivian Amazon, when forest fires, for example, occur.

“Women suffer much more in conflicts (wildfires), they are disproportionately affected and another thing to think about is just how they manage their menstruation when there is no access to water,” she reflects.

Women from San José de Chiquitos, in a conversation with Yawar in 2024, stated that as a result of the forest fires, water in that region “was becoming scarcer”, so when this situation arises they have to walk much further to access this vital resource.

“Who has to fetch water, whether for cooking or bathing, is going to be the woman, in many cases the girls. And traveling many kilometers alone subjects them to other situations of vulnerability, including sexual violence,” Oropeza said.

Get to know her before she arrives

Just that day, Leydi S.’s parents had gone out, leaving her alone. Upon entering the bathroom, she discovered to her surprise that her underwear were stained with blood. Her body shuddered, but she remembered the few times she had heard about this at home and at school.

“When I saw the blood, I was so terrified, I was so scared,” she recalls. So was her experience at age nine, when she had her first menstruation.

Now, at 15, she reflects on the fear she felt then, a common feeling among many girls facing their first period. However, she recognizes that menstruation is as normal and natural as breathing or digesting food.

Leydi S. is in the fourth year of secondary school at the Elizardo Pérez Educational Unit. In the teachers’ room, not only she, but also a group of classmates, both girls and boys in the first, fourth and sixth grades of secondary school, were encouraged to talk about menstruation with ABI.

“The moment it happened to me, I got scared and felt a lot of anguish, but then I understood that it is nothing bad (…), it is something natural that happens to all women,” says Guisel H., also a fourth grader in high school.

According to the aforementioned teacher’s guide on Comprehensive Sexuality Education, “menstruation is commonly called period, chapulín, andrés ‘because it comes every month’, la luna, estoy en esos días, me bajó/me vino, indispuesta, la prima roja and many others”.

“These euphemisms are used because menstruation is a term that is little verbalized, due to taboos. Menstruation is stigmatized as a sign of impurity, of something dirty, therefore it generates shame, giving rise to the use of a number of euphemisms,” she says.

Marcelina Mamani, a 57-year-old blind woman, began menstruating at age 13 and entered menopause (the phase in which menstruation ends) at age 48. During the 35 years she menstruated, she believed it was “bad and useless blood.

“My older brother told me about this: ‘some people get scared, you don’t have to get scared,’ he said,” she says while offering lottery tickets, accompanied by her husband, also on the sidewalk of Mariscal Santa Cruz Avenue in the metropolis of La Paz.

Marcelina has been visually impaired since birth. She is a native of Cochabamba. She has two children, a boy and a girl. It was she who explained to her daughter, who is now 34 years old and has two children, that menstruation is a normal part of a woman’s life.

In several Bolivian cultures, menstruation is usually a secret or not very verbalized topic, and it is also mainly the responsibility of mothers to provide guidance and indicate the care that adolescents should take during the menstrual period.

For example, in the Yaminawa culture, menstruation is a secret. In the Yuki and Tacana culture, only mothers are the ones who guide their daughters before they have their first menstruation. In the Tsimane culture, it is also a secret.

In some cases, the adolescent (usually the eldest daughter) experiences menstruation alone with the fear of bleeding, and then informs her mother, who guides her in the subsequent care. If the mother has other daughters, before the menarche she orients them beforehand.

Nelson Yujra, president of the School Board of the Elizardo Pérez Educational Unit, recognizes that many parents, at least in this school, “are a little closed” to talking about menstruation with their daughters and sons.

She is included in revealing that her three daughters learned about the subject from their mother and among sisters, due to the fact that “among women there is more trust”; however, she considers that it is out of fear or shame that many fathers do not dare to talk to their daughters about it.

Certified menstrual educator, Yazmin Salas, from Costa Rica, in a Webinar organized by MSI Bolivia Marie Stopes, in August 2023, considered “that there is no minimum age to talk about menstruation with children, but it is important to address it when they are eight and nine years old”.

“It’s never too early and never too late to talk about menstrual education. If I have a two-year-old and I change my pad in front of her and she asks me, I can answer naturally so that she knows that this topic can be talked about at home,” she recommends.

For the Clinical Manager of MSI Bolivia Marie Stopes, Silvia Velasco, it is “extremely important” that before menstruation arrives, girls understand that “it does not mean that they are becoming little women”, but that it is a biological process they are going through.

The biggest fear: staining

Unicef’s Ureport survey revealed that 47.7% of those consulted did not miss school because of menstruation, but 45.2% stopped going to school because they felt pain and discomfort when going through this biological process.

On the other hand, 31.4% said they felt fear when it was their first menstruation, 16.3% felt embarrassment, 15.6% nothing special, 12.6% worry, 6.7% uncertainty, 4.7% indifference, 3.1% joy and 2.2% sadness.

(Read the complete report in ABI).