La Paz, Mar. 08, 2025 (ATB Digital) – Maternal death in Bolivia continues to be one of the most invisible tragedies faced by the health system, especially in rural and remote areas of the country. In February of this year, a 19-year-old woman, nine months pregnant, lost her postpartum life in a remote area of the Amazonian municipality of Puerto Rico, in the department of Pando. This unfortunate event highlights the serious inequalities in access to health services and the importance of making timely decisions in situations of risk.

The young mother decided to work in the chestnut harvest with her partner, unaware that her life and that of her baby would be threatened by complications related to childbirth. In a precarious environment, far from medical centers, the birth was attended by a woman in charge of the shack, who, together with other women, performed the procedure without adequate assistance. After the birth of her baby, the placenta did not deliver and dangerous bleeding began. Despite efforts to transport her to the nearest health center, the young mother died en route, approximately 14 hours after the onset of labor.

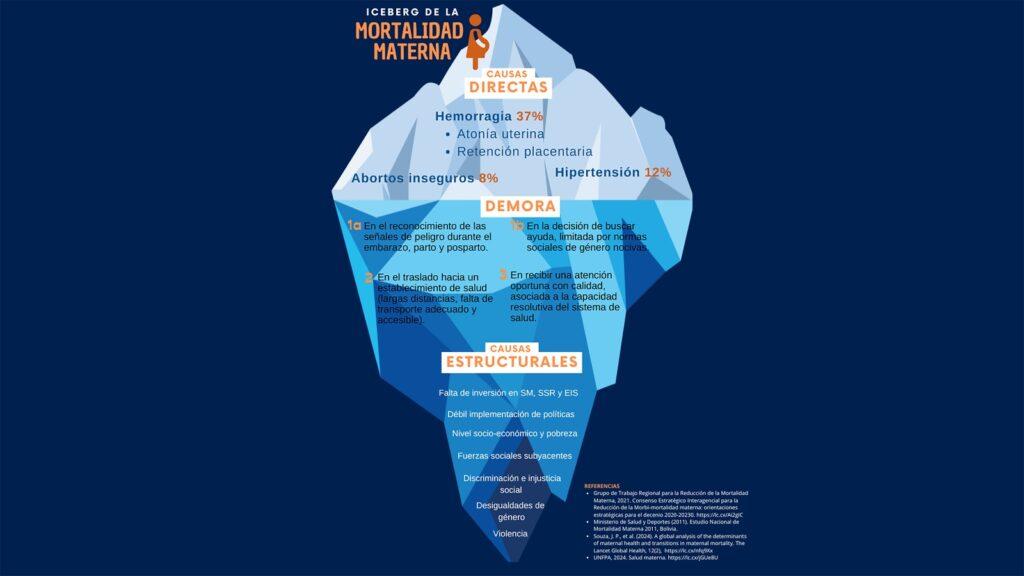

This case clearly illustrates what is known as “delays,” a determining factor in the increase in maternal deaths. In this specific case, the first delay was in recognizing signs of complications during pregnancy and childbirth, such as bleeding, and in making decisions to seek appropriate medical care. The second delay was related to the transfer to the health center, considering the distance that separated the patient from the appropriate place for care. Unfortunately, when she finally arrived at the medical service, she had already passed away. However, it is crucial to ask whether the health center had the necessary resources to provide timely and effective care.

Maternal deaths in Bolivia reflect the deep inequality and inequity in society. In Latin America and the Caribbean, approximately 8,000 women die each year from preventable complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (UNFPA, 2023).

The National Maternal Mortality Study Bolivia (2011) identifies that 68% of maternal deaths are among indigenous women, which underscores the disparities in access to health services and quality of care, especially for the most vulnerable populations. It also states that the main causes of maternal mortality in the country include hemorrhage (37%), hypertension (12%), unsafe abortions (8%) and infections (5%). However, the reality is even more complex and, many times, only the “tip of the iceberg” is seen. Behind every maternal death, there are significant structural barriers that contribute to the tragedy. The distance of rural communities from health centers, the lack of adequate transportation, and the shortage of trained personnel are some of the factors that aggravate complications during pregnancy and childbirth.

Despite the fact that 85.6% of pregnant women in Bolivia receive at least four prenatal checkups (EDSA, 2016), huge gaps still persist in terms of access, quality and coverage of health services. Women living in rural areas, especially indigenous women, suffer the most from these inequalities, with limited access to quality care and optimal resources to ensure their safety during pregnancy.

UNFPA and other international organizations have pointed out that all maternal deaths are preventable, and it is important to address the real barriers that limit access to medical care. The response must be comprehensive, involving families, communities and health systems, to promote information, education and behavioral change processes to address the risks faced by pregnant women. It is also necessary to strengthen the transportation system and ensure that women have access to timely care, especially in rural and hard-to-reach areas.

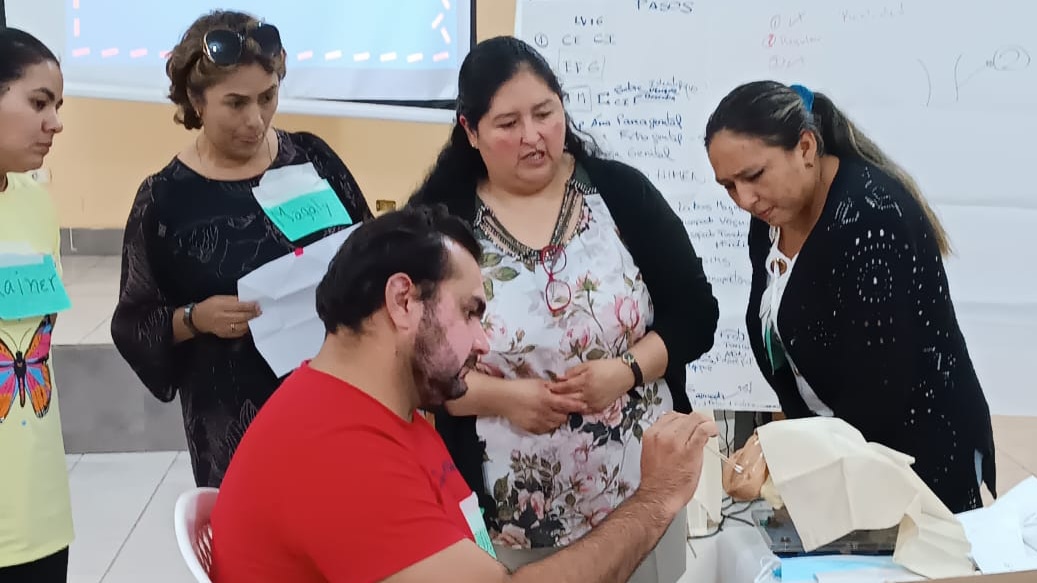

The case that arose in Pando should serve as an urgent call to strengthen public health policies, with a focus on equity and universal access to quality services for all women, regardless of their geographic location, ethnicity or socioeconomic status. Within this framework, the Ministry of Health and Sports is currently implementing the “Action Plan for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal, Perinatal and Neonatal Mortality in Bolivia” with the premise of expanding access to essential, comprehensive, quality interventions in maternal, perinatal and neonatal care. This Plan is based on an equity, intercultural and intersectoral approach with social participation and an inclusive approach. The implementation of this Plan emphasizes the improvement of information processes and systems, epidemiological surveillance of maternal, perinatal and neonatal mortality at all stages, to achieve timely decision-making and interventions.

Maternal death should no longer be an invisible tragedy, but a reality that mobilizes society and authorities to act to prevent further losses.

Ultimately, every life that is lost is an opportunity that is lost on the road to building a fairer, more equitable and healthier country. All women, especially the most vulnerable, must give birth in conditions of dignity and safety, safeguarding their lives.

March 8, International Women’s Day, is a key date to reflect on the progress and challenges in the struggle for gender equality, but also to highlight persistent problems affecting women, such as the high maternal mortality rate in many parts of the world. The quality of access to health and sexual and reproductive rights continues to be a global concern, especially in countries with high rates of poverty and inequality. In this context, we have a valuable opportunity to strengthen efforts for gender equality and women’s empowerment, guaranteeing the full exercise of their rights, sexual and reproductive rights being the most human of all.

References:

- UNFPA (2023). Joint statement in favor of reducing maternal morbidity and mortality. https://acortar.link/QUJJj8

- Ministry of Health and Sports (2011). National Maternal Mortality Study 2011, Bolivia.

- National Institute of Statistics (2016). Demographic and Health Survey EDSA 2016.