In one of his first group therapies in the Men of Peace program, Ronald broke down and admitted that he was violent. At first, he showed resistance and even asked: “I’m not crazy, why did they send me here”. Day after day, and after listening to the testimonies of 11 other men denounced for domestic violence, he dared to tell the truth and revealed that he had mistreated his wife and children.

“I’m not telling the whole story. I would come home from work angry and what I usually did was yell,” said Ronald and began to tell how he came to be denounced for domestic violence by his wife. From the day he recognized that he had a problem, he attended all the therapies, concluded the program, recovered his family and resumed his projects. Today, he emphasizes that thanks to the therapies he stopped being a violent man and became a man of peace.

For Germán Siles Heredia, general director of Hombres de Paz, which depends on Fundación Voces Libres, Ronald’s story is an example of the results achieved by the therapies and a reason to continue with this program. “There are many similar testimonies”, he explains and clarifies that there is a minimum recidivism rate.

Since its creation seven years ago, the Men of Peace program has attended to 6,300 men, and of that total, the number of recidivism cases is minimal, according to a study carried out last year by the director. “I’m talking about 20 cases that have reoffended out of the total of 6,300,” Siles says. This figure is equivalent to 0.32%.

In addition to following up on cases, this institution identifies cases of recidivism because the men return to Hombres de Paz, file a new complaint with the Prosecutor’s Office after closing a first case or call from prison to channel therapies.

The other men who have completed therapy at Hombres de Paz, or 6,280, have not reoffended, emphasizes its director. In addition, no case has reached the level of femicide.

The origin of everything

Hombres de Paz has been in operation for seven years and was born with the objective of finding the answer to the question of how to prevent more acts of violence against women by working with the main promoters of these crimes: men.

“We made a situational analysis, we also saw the intersectoral coordination we have with other institutions, (we saw then that) many have focused their attention -since the promotion of Law 348 (Integral Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence), 10 years ago- on working with women”, Siles assures.

According to the specialist, while attending to women survivors of violence and their families, a service provided by Fundación Voces Libres, they realized an important fact. “(What) they were looking for with the denunciation was for their husband to change, what they were looking for with jail was for their husband to leave and become a new man or new person, but that change is not possible only with the sanction or by telling him: ‘I have denounced you’, but there has to be therapeutic work with these men,” she explains.

“We basically seek to generate changes in their ways of thinking, feeling and acting so that they can reflect and deconstruct their social-cultural construction,” says Siles, in reference to the fact that this program shows aggressors “how they can relate to the other gender and solve their problems in the best way possible, without resorting to violence”. “Our progress has been marked by the testimonies,” he adds.

Hombres de Paz currently has therapeutic centers in the cities of Cochabamba, La Paz and Potosí. The teams are made up of clinical psychologists and specialists in the social area.

The therapeutic center in La Paz was set up two years ago. “At the beginning, the idea was to work in the same way they did in Cochabamba or Potosi, but the reality of La Paz is different. It is almost the same power as Santa Cruz, because in La Paz there are many cases. You only have to remember that in 2023 there were 22,000 reports of domestic violence. That’s a lot,” says the regional coordinator of the Men of Peace Project in La Paz, Jesús Calle.

For feminist, activist and journalist Patricia Flores, the initiative of the Hombres de Paz therapeutic center is undoubtedly a fundamental step in the fight against violence against women. “This perspective finds its basis in the conviction that to effectively address this problem and work with men, because they too are victims of a violent and cruel system such as patriarchy and dismantle the macho structures that have been internalized over millennia,” she says.

Flores explains that “the misconception that men should be strong, not cry and maintain a constant appearance of power has contributed to the construction of toxic masculinities.” “Toxic masculinity is a set of social mandates that perpetuate violence, domination and the exercise of power through force. This approach creates a vicious cycle in which men are socialized to repress their emotions, use violence as a means of control, and maintain a status of superiority.”

Every year, crimes under Law 348 (Integral Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence), are on the rise. In 2022, 51,401 cases were registered, while in 2023 the figure closed with 51,770, which reflects an increase of 369, according to a report from the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

According to the State Attorney General, Juan Lanchipa Ponce, of the 51,770 cases, the most reported crime at the national level is Family or Domestic Violence with 39,096. It is followed by Sexual Abuse with 3,866, Rape with 2,999, Rape of an Infant, Child or Adolescent with 2,803, Rape with 1,782, Sexual Harassment with 366, Abduction of a Minor or Incapable with 356 and Economic Violence with 149, among others.

Three groups

Who benefits from the Men of Peace program? They are divided into three groups: men referred by the Prosecutor’s Office and the Courts after being accused of the crime of domestic violence (Article 272 bis Bolivian Penal Code); those referred by the municipal integral legal services (SLIM) in accordance with an agreement; and those who come voluntarily and admit that they face marital relationship problems due to violence.

This program provides therapy specifically to men who have committed the crime of domestic violence. “We do not treat other typologies such as rape, sexual abuse and femicides, we only focus on 272,” explains director Siles.

“Our whole approach is aimed at generating significant changes in their lives and that these people are our spokespersons outside, because if we transform a man, we are ensuring that his children will no longer replicate these behaviors. Maybe then we will be able to have a generation without these tragic behaviors, such as taking the life of a loved one, whether it is a wife, a mother or a daughter,” he adds.

Some come by court order as an alternative sanction and if they fail to comply, the measures are revoked and they could even go to jail. Others arrive by prosecutor’s order as protective measures, they are denounced and while the cases are investigated, they have to attend therapy.

The regional coordinator of the Men of Peace Project in La Paz, Jesús Calle, explains that the Voces Libres Foundation has an inter-institutional agreement with the Departmental Court of Justice. “They refer the cases to us with fiscal requirement, since article 272 of the Penal Code indicates the protection measures, in which the authority can request that the denounced person goes through the Rehabilitation Centers for aggressive behavior. Article 31 of Law 348 (Integral Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence) also indicates this”, he said.

Calle clarifies that therapy does not supplant punishment. “This is something we have to inform the users, because they say: I’m just doing my time, I’m innocent, and that’s not the case, therapy is not forensic, therapy is something else,” he assures.

In the case of the group of volunteers, Director Siles emphasizes that they came to the program “after hearing about Hombres de Paz in the media and social networks.” “They have decided to do therapy and have returned to their families, to their family and work environment. They have seen that being effectively in Hombres de Paz, five or six months, 18 or 24 sessions, has helped them build their lives,” he comments.

“This gives us greater conviction to continue with the program because what Hombres de Paz basically seeks is to increase the security and wellbeing of families, that is, if we transform the mentality of a male aggressor or a man who commits violence, we are protecting a woman. What we want is that he does not reoffend and does not commit this crime again, either with the ex-partner or with the new partner”, adds Siles.

The regulations

With the objective of contributing to the rehabilitation of aggressors, in application of Article 31 of Law 348 (Integral Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence), Fundación Voces promoted the creation of the program Hombres de Paz (Men of Peace). After seven years of work, it has become a pioneering institution in providing psychological care to violent men.

According to Article 31 of Law 348, “the rehabilitation of aggressors, by order of the competent jurisdictional authority, will be arranged by express order, with the objective of promoting changes in their aggressive behavior. The therapy will not substitute the sanction imposed for the acts of violence”.

The regulation establishes that rehabilitation services may be organized through intergovernmental agreements, both in urban and rural areas, in existing centers or where the aggressor is serving a criminal sentence. In addition, those responsible for these services must report the start, compliance or non-compliance of the program or therapy by the aggressor to the competent jurisdictional authority and to the Plurinational Integral System for the Prevention, Attention, Punishment and Eradication of Gender Violence (SIPPASE).

The director of the Casa de la Mujer in Santa Cruz, Ana Paola García, explains that article 31 of Law 348 also aims to implement rehabilitation services in both urban and rural areas, in the urban-rural area through community methodologies programs, but the truth is that they have not even managed to comply with the services of integral recovery and integral reparation of the damage to women.

“We do not have public services to address mental health issues, the aftermath of violence. We do not have public spaces that guarantee processes for women to have access to psychological therapies that are aimed at curing or healing in a comprehensive manner the wounds caused by violence. And much less do we have centers where rehabilitation for aggressors is provided free of charge and in a public manner,” says Garcia.

For the former Director of the Penitentiary Regime, Ramiro Llanos, rehabilitation services for men detained for domestic violence in the country’s prisons are almost non-existent. He explains that, instead of improving the behavior of the men, they are becoming more violent in the prisons.

“We are forming monsters. I have said it before: a law against violence supposedly punishes violent people by taking them to prison, but our prisons are violent,” says Llanos, who says that, in the prisons, “the way to survive is to be violent”.

“Unfortunately, people think that the best thing to do is to put the person in jail, but there they don’t have any kind of therapy. On the contrary, what happens is recidivism, he gets out and hits his partner again,” she says.

How does it work?

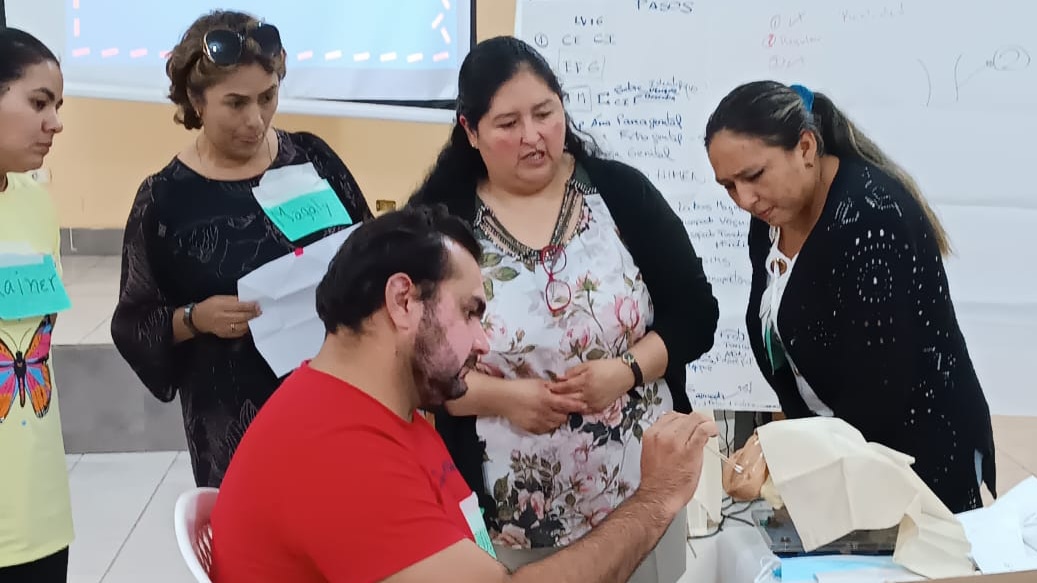

The Hombres de Paz program offers individual and group psychological therapies, alternative therapies and social follow-up to family members, among other services.

According to Siles, the group psychological therapies create a space to “reflect and question everything that affects the participants, all the behaviors they have done to become Men of Peace, but at the same time they are shown how all this affects the lives of their partners and children, how it affects their social, work and civil lives, and all the consequences of violence by a man are shown.

This work dynamic works on the basis of one of the program’s main missions: a beneficiary “must leave with something, with a seed in his thinking and in his way of being, that he will think twice before making the same mistake again”.

In the sessions they not only talk about the importance of good treatment and the characteristics of the Law against violence against women, but also about the benefits of therapy. “That is to say, what I gain if I change and how it harms me if I continue to support these behaviors,” explains Siles.

For the specialists of this program, it is important that the men understand that psychological therapy is not a sanction, but “it is an alternative, a second chance for them and their family environment to improve”. This is how Ronald understood it.

Sessions are once a week, each session lasts two hours. The groups are open and are of 12 people.

In therapy, a beneficiary can listen to the stories of 11 other men. For the specialists, this dynamic is key because there are some who have been in the group for 10 sessions or others who are newer.

How does this dynamic work? In one session, Juan tells his companions: “if you follow my path, you will end up in jail, I thought the same as you, I beat my wife because I thought she was my property, that’s wrong”.

According to Siles, “these life testimonies make others recognize that they have a problem. In addition, the aim is for them to assume the responsibility of making amends, which means that they can see things differently.

For feminist and activist Patricia Flores, the Hombres de Paz initiative seeks to unravel these harmful patterns by offering a therapeutic space that encourages reflection, deconstruction of gender roles and learning about non-toxic masculinities. “By working with men, we seek not only to change individual behaviors, but to transform the cultural and social structures that perpetuate gender-based violence.”

“The active participation of men in this process of change is essential to build a more equitable and violence-free society. The commitment between men and women in the fight against gender-based violence is an indispensable step towards building a culture based on mutual respect, equality and the understanding that all human beings, regardless of gender, deserve to live free of violence and discrimination,” explains Flores.

Currently, Hombres de Paz has 24 therapeutic groups in Cochabamba, each serving an average of 15 people. In La Paz they have a similar number and in Potosí they have 12 groups.

The average number of sessions is 24, but if the psychologist sees that the participant does his part, shows predisposition and wants to improve his life, he has the possibility of leaving the program earlier. He/she must attend a supervision that can be every 15 days or monthly.

The specialists also offer individual therapy. This service is given especially to men who arrive with a cognitive distortion that the woman is the problem, think that they are victims of justice and begin to put themselves in a position of resistance.

It is not only a matter of complying with the 24 sessions ordered by the court. The Hombres de Paz team makes an evaluation and talks to the beneficiary, asking him how he evaluates his participation in the process. In this conversation, it is explained to him that he has complied with the number of therapies, but that his performance was not the most suitable.

“The psychologist will tell him: “I saw in the sessions that you don’t want to do your part to solve this issue”. In that conversation he is informed that the team saw fit that he has to follow the time determined by the court, which is generally one year. In this case, he must comply because his freedom is at risk.

In the Prosecutor’s Office, when accused, they are sent to sessions of two or three months, the time varies. In this group, some of them reach a conciliation or the partners present a withdrawal, then they leave the sessions due to these circumstances.

Volunteers have access to 12 or 18 sessions, there is no limit. Everything varies from case to case, there is no rule, it is not like getting promotions, it is not like passing school and no grade is given. What is done is a closing interview, in which the men give a life testimony about how they have arrived at this process and how they are leaving. This step “gives the lights” to say if he is ready or if he needs to stay longer.

Follow-up

The Men of Peace team corroborates each case with a social visit, which basically consists of inquiring how the male has been in the last six months or the last year, after having completed therapy.

In the follow-up, the team talks with the man and his family. “We have listened to them, we have seen them and we have gone to visit them in their homes, many tell us: ‘I am already different, I am already a better father, I am already a better husband and I am already a better man,’” says director Siles.

Many men return or reconcile with their partners, others learn to respect the decision of ex-partners or ex-wives who no longer want to resume the relationship and move on with their lives.

The challenge

In seven years, Hombres de Paz served 6,300 men. Of this number, 50% were referred from the Prosecutor’s Office, 40% were referred from the Courts and 10% were voluntary.

Court cases are increasing and these men who committed the crime see the program as a second chance, knowing that, if they fail to comply, the detention measures can be revoked.

For Siles, the challenge is to increase the percentage of the volunteer group. “If this 10% were 40%, we would be talking about a great advance because what we want is for men not to go to these extremes. If a man comes voluntarily, it is because he is having problems with discussions (…),” he says.

By taking the first step, that is, by recognizing that he has a problem, the man has the possibility of accessing a psychologist, who will give him the skills and tools to reflect and analyze his situation. “The possible solutions are in him, if he recognizes that he is the problem, he will be able to change,” he concludes.